Reusing manure is no new thing. Some 8,000 years ago, the first European farmers started to use the dung of their livestock to fertilize crops. No doubt the ancient Egyptians had done so already ages ago. In some regions still today, cow dung is used as building material or as fuel. But do you know what happens to human waste?

Kemira’s products are used to purify the equivalent of 320 million people’s annual water usage.

The public service that we take for granted

Your flushed waste travels to your local municipal wastewater treatment plant. Their job is to separate the solids from the liquids and clean the water, usually with the help of chemistry, so that it meets strict regulations and can be returned safely back to the water cycle. It is a great public service. Kemira’s products are used to purify the equivalent of 320 million people’s annual water usage. But what happens to all those solids?

The solids, or the so-called sewage sludge is loaded into big tanks called anaerobic digesters. Here, the temperature it is kept at 35°C and the sludge is mixed with bacteria to break it down. As the bacteria digest the sewage, the first opportunity to make something valuable from our waste presents itself: biogas (mainly methane) can be produced. The biogas can either be piped into large engines which produce heat and electricity or refined into > 99,9 % pure methane, which can then be exported to the national methane grid or even used as a vehicle fuel.

One of the key objectives of the sludge handling process is to make the sludge as dry as possible. This will make it easier to handle and reduce the transportation costs. There are different ways and equipment for doing this, and again, chemistry helps. But really the big question is: where does the dry, treated sludge finally end up in?

What if….?

In many cases, sludge is shipped to a special facility and incinerated, smoked into the thin air – wasting all the valuable nutrients (like phosphorus) and iron with it. There are methods to recover nutrients from the ash obtained after combustion, but these are not yet widely used. At the same time, economically recoverable phosphorus – an essential plant nutrient required for growth – may, according to some estimates, run out by the end of this century. Even if this dramatic scenario does not materialize, the easily accessible sources are located in countries like Morocco and Syria, which is not entirely unproblematic. At the same time, in some locations like the Nordics, agricultural soils are depleted in organic matter and nutrients.

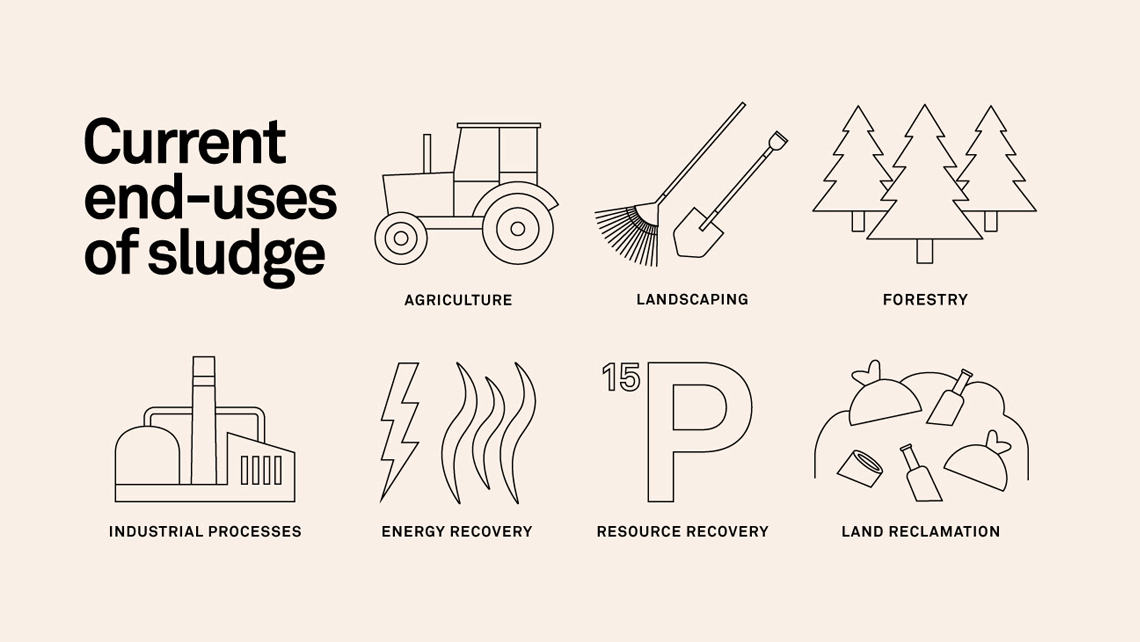

In some cases, like in some states in the USA, the conditioned, dried, and pelletized sludge is bagged and sold as fertilizer for your garden lawn or golf courses. Other end-uses include e.g. landfill disposal, urban landscaping, forestry and agriculture (mainly as fertilizer for animal feed crops). But much of this “waste” that contains value is today more or less wasted.

It is with the food-chain that we step into sensitive territory. Therein lies the challenge: pathogens (micro-organisms that can cause disease), microplastics and pharmaceuticals that may or may not be sufficiently removed by the existing treatment methods are all cause of public concern. The use of treated waste from wastewater plants in soil and growing crops for human consumption has both real challenges as well as those more related to branding, sentiments and public awareness – or the lack-of.

One thing is sure: we are a clever species and tend to find solutions to challenges when motivated to do so.

However, one thing is sure: we are a clever species and tend to find solutions to challenges when motivated to do so. We’re already recycling urine to drinkable water on spacecrafts. On the movie The Martian, an astronaut becomes stranded on Mars after his team assume him dead. He manages to keep himself alive by crowing crops from an old potato and his own waste. May sound like sci-fi fantasy. What if we managed to develop ways to safely do the same? Sludge disposal is a huge cost for modern societies and taxpayers – you and me. What if we really focused our efforts on finding ways to turn this cost item into a resource with value?

This DOES concern you and me

One thing good to remember, of course, is that our level of sanitation and the sophisticated treatment methods of wastewater and sludge are by no means a given all around the world.

Almost 40% of the global population still today live without proper sanitation and any such systems. And it is the population in those regions that is growing the fastest. This means that, like it or not, in addition to starting to ask questions about the disposal of our own waste, we need to take interest in the waste of others. It is the only way to ensure our planet can handle the strain we put on it – and to improve public health overall. Much of this is driven through legislation and the effective enforcement of regulation. But we, you and me, have powers to influence this.